My life would be easier if people would use both first name and surname when naming dishes after people — like Toast Pelle Janzon. Yes, you guessed it. Just as we’ve seen with Biff à la Lindström, there’s more than one Wallenberg who is said to lend their name to this hefty veal patty called Wallenbergare.

Click here to skip straight to the recipe for Wallenbergare.

Who’s the Wallenberg behind Wallenbergare?

Luckily, I received help when trying to bring some clarity into the matter of who the “real” Wallenberg really was. I would like to express my gratitude to Grand Hôtel’s restaurant Verandan, Wallenbergsarkivet, and Riksarkivet for contributing to this article.

Now, let’s take a look at the theories.

Theory #1: Amalia Wallenberg, née Hagdahl

The first theory is that the veal patty Wallenbergare got its name from Amalia Wallenberg (1864-1959). She was the daughter of doctor and famed cookbook author Charles Emil Hagdahl, whose cookbook became a big hit in the late 19th century. Amalia Hagdahl married Marcus Wallenberg Sr. in 1890.

I first reached out to Stockholm luxury hotel Grand Hôtel’s restaurant Verandan to see if they could assist me with the research, for two reasons:

- The Wallenberg family’s company Investor AB owns Grand Hôtel, through The Grand Group. Peter Wallenberg Jr. used to be the CEO of the hotel. Meaning, the hotel has a connection to the Wallenberg family and therefore, possibly, to the source.

- I’ve eaten delicious Wallenbergare there. They were decadently creamy, making it a strong coffee and something sweet necessary afterwards if you didn’t feel like a nap to sleep it off. Being skilled at making them counts for something, yes?

Grand Hôtel turned out to have a heavy ace up their sleeve:

Support from Tore Wretman

Grand Hôtel kindly shared this story that they had gotten from Tore Wretman, one of the chefs who modernized the Swedish kitchen. Although he died in 2003, Wretman is still one of the greatest authorities as it gets when it comes to Swedish cuisine.

According to Wretman, the recipe “probably” came from Charles Emil Hagdahl “although it didn’t appear in his Kokkonsten from 1873″. Wretman considers the dish an evolution of the Russian chopped veal fillet Pojarski. That dish got its name from a famous chef at the Romanov court.

Wretman had a recipe where sweetbread was substituted for a quarter of the veal, and considers it superior. Apparently, Wretman’s first contact with Wallenbergare was through chef Arthur Nyh at Riche. Nyh had previously worked with chef Julius Carlsson at the restaurant Cecil. Wretman had confirmed the recipe with Marcus Wallenberg, who had been involved in Wretman’s restaurants.

Analyzing the evidence for theory #1

So, what conclusions can we draw from this story?

- The actual origin of the recipe and the name isn’t clarified very well by Wretman. “Probably”?

- Wretman creates a connection to the restaurant Cecil and its head chef Julius Carlsson, through Arthur Nyh at Riche.

- Amalia was just a little girl when the first edition of Hagdahl’s Kokkonsten came out. It’s no wonder it didn’t feature a recipe called Wallenbergare. It had somewhat similar recipes, though.

Interesting. Let’s take a look at the second theory:

Theory #2: Marcus Wallenberg Sr.

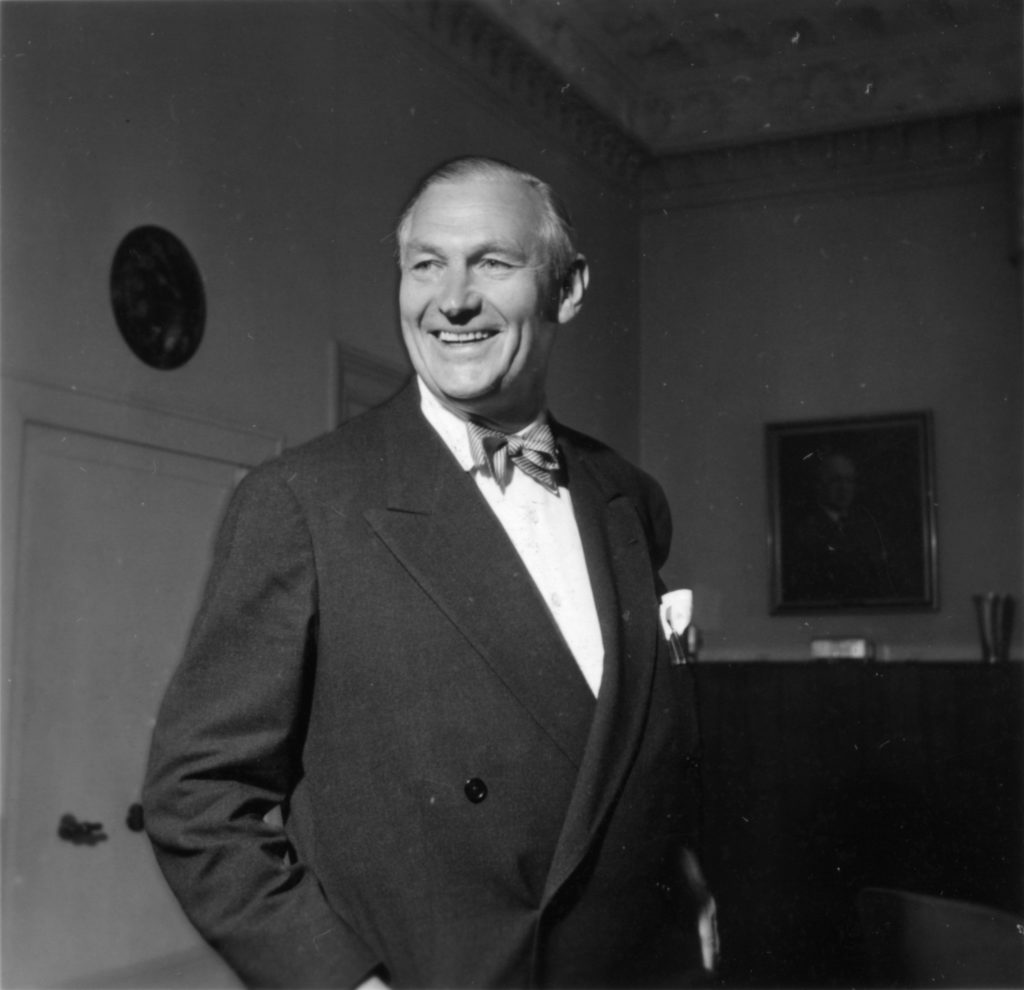

Marcus Wallenberg Sr. (1864-1943) was a vice district judge and CEO of the Swedish bank Skandinaviska Enskilda Banken, SEB. He married Amalia Wallenberg.

Wallenbergsarkivet was kind enough to share the following story:

“One of the stories is that Marcus Wallenberg Sr. came to his regular table at restaurant Cecil in Stockholm. He had just returned from a trip to the continent, where he’d had a wonderful chopped veal fillet. Marcus asked the head chef Julius Carlsson to make something similar. The legendary chef Julius Carlsson, feared by many chefs and known for his hot temper, accepted the challenge and cooked what we today call a Wallenbergare.”

Apparently, Peter Wallenberg Jr., former CEO of Grand Hôtel in Stockholm, tells this story.

Analyzing the evidence for theory #2

So, what are the conclusions?

- The restaurant Cecil and its head chef Julius Carlsson play a part in this origin story as well.

- This theory has a more developed origin than just “probably” being from someplace.

- Peter Wallenberg Jr., the great-grandson of Peter and Amalia Wallenberg, tells his story.

Theory #3: Marcus Wallenberg Jr.

I thought all was well when I learned of a third theory through an interview with chef and restaurateur Peter Nordin. Then Riksarkivet had shared the same story on Facebook. Studying parts of Julius Carlsson’s archive at Riksarkivet, I found out a few interesting things…

This story is similar to the second, but here it is instead Marcus Wallenberg Jr. (1899-1982) who is the person who inspired the veal patties’ name. He was the son of Amalia and Marcus Wallenberg Sr.

So, the third theory, according to the article “Wallenbergare” — En hackad kalvfilé, dess historia, tillagning och servering, by Sune Carlqvist in Gastronomisk guide:

In the mid-30s, “doctor Marcus Wallenberg” and bank manager Rickard “Julle” Julin came to the restaurant Cecil and their regular table, nr 37. They had recently returned from a trip to the continent and gently teased the headwaiter, Gustaf Litzén, about the marvelous chopped veal patty they’d eaten — they’d never get anything like that in Sweden… Litzén went to the kitchen and told chef Julius Carlsson about the conversation, and Carlsson responded by creating Wallenbergare. While the dish was Carlsson’s invention, Litzén named it.

Analyzing the evidence for theory #3

Let’s evaluate the findings.

- The article writer, Sune Carlqvist, claims to have verified the story with Julius Carlsson’s boss Allan Hasselmark, with Gustaf Litzén, and even with “doctor Marcus Wallenberg”. The author is likely the same Sune Carlqvist who worked with and trained as a chef under Julius Carlsson. From the archive at Riksarkivet, it is also evident that Julius Carlsson and Sune Carlqvist wrote a few articles about food together — meaning, Sune Carlqvist had good access to “the source” Carlsson.

- The Julius Carlsson archive contains two articles about Carlsson with this version of the story. While I have only gone through the parts of the archive deemed most relevant, the fact that Carlsson had kept the articles and no other story increases their credibility. Carlsson seems to have agreed with their conclusion.

- The article names “doctor Marcus Wallenberg” as the Wallenberg in question. Marcus Wallenberg Jr. got a Technical Honorary Doctorate at Tekniska Högskolan in 1957 and became an Honorary Doctor of Economics at Handelshögskolan in Stockholm in 1971. Although his father received many awards and honors, he was not a doctor. Wallenbergsarkivet kindly confirmed that the title “doctor” was used by Marcus Wallenberg Jr. and not his father.

- While Rickard “Julle” Julin worked closely with Marcus Wallenberg Sr. for many years, Marcus Wallenberg Jr. was elected into the board of the bank in 1927 and a biography of Julin mentions how he and Marcus Wallenberg Jr. were working closely together in 1932. It’s not unlikely that they traveled together at the time.

So, which theory is right?

Who knows. Either case, it is all in the family. I’d say the bet is between theory number 2 and number 3. Personally, I believe the third theory gains credibility from (according to the article by Carlqvist) being verified by both Julius Carlsson and Marcus Wallenberg Jr.

My suggestion? Just say that Wallenbergare are named after Marcus Wallenberg. You’ll most likely be right — at least as long as nobody asks you to specify which one…

Either way, it is an impressive dish.

To add to the story, chef Peter Nordin thinks he’s found the place where Wallenberg ate the patties that inspired Wallenbergare. Apparently, it is a butchery with a dining space, called Chez Benoit.

What is a Wallenbergare?

Wallenbergare are veal patties, made with plenty of whipped cream and yolks.

I’m always pleased when I find people who are more obsessed with a relatively obscure topic than I am. In their thesis Wallenbergare — En jämförelse i sensorisk kvalitet, Elsa Lansing, Tove Wedin and Malin Widén share their findings.

The conclusion was that you achieve the best “sensorial quality” when mixing 75% veal with 25% sweetbread, together with yolks and cream. It should only be flavored with salt and freshly ground white pepper. Ingredients should be kept cold and you should mix them together mechanically.

However, there doesn’t seem to be much of a quality difference in using all veal compared to swapping a quarter of the veal for sweetbread, or in using ready-ground veal compared to grinding it yourself.

Wretman’s approach to flavoring

Tore Wretman flavors his Wallenbergare with a spice mix called épice Riche. The spice mix is Wretman’s own, named after a restaurant where he worked. According to the recipe shared by Grand Hôtel, épice Riche consists of one measure ground nutmeg, two measures ground white pepper, one measure ground allspice, and one measure ground cloves. However, the Wallenbergare-thesis concludes that the spice mix overpowers the flavor of the meat. Using épice Riche is hardly true to the original recipe, but rather Wretman’s version of the patty.

According to the article in Gastronomisk guide, a Wallenbergare should weigh 125 grams before you fry it, and it will lose about 20 grams of its weight during frying. Both Wretman and Carlsson seem to use the same cooking method, frying the patties (only flipped once) until they are done. The Wallenbergare-thesis uses a slightly different approach, letting the patties brown and then baking them in the oven at 150°C until they reach an inner temperature of 70°C (though I’ve seen different ideas on the temperature, ranging between 58°C and 70°C).

Two tricks for succeeding with Wallenbergare

Welcome to Kitchen Chemistry — intermediate level. Today’s lesson is fat emulsions.

So, how much cream can you put in a veal patty like Wallenbergare and still make it hold together?

To pull off successful veal patties, you’ll need to:

- keep the ingredients cold, and

- use a hand mixer or stand mixer.

According to the Wallenbergare-thesis, the ideal temperature for blending the meat together is 7,2°C. If the temperature of the mix is higher than 21°C, you risk that it curdles. Keep all ingredients cold, and you’ll succeed.

Then, there’s the mixing of the ingredients. To create the emulsion, you need to mix the meat “mechanically” and not with handcraft. I wish I’d read the Wallenbergare-thesis before I started cooking my first batch because it didn’t really want to come together. For the second batch, I used a hand mixer, and that made all the difference.

How to serve Wallenbergare

Julius Carlsson will have to forgive me. According to the article in Gastronomisk guide, he states that you should absolutely not serve any lingonberries with this dish. As the lingonberries are mentioned, we’ll have to assume that they had already “became a problem”. So, while the lingonberries aren’t original, they are a pleasant addition, but don’t feel bad if you don’t have any on hand! You’ll just be a bit more traditional.

The article doesn’t mention the small green peas who are popular to serve together with the dish. They are probably a later addition, as well. Wretman does serve his Wallenbergare with both lingonberries and green peas, so at least the combination gets his seal of approval.

According to the Gastronomisk guide, you should serve your Wallenbergare with Pommes Mousseline. That’s potato puré made with pressed potato, cold butter, and heated cream, flavored only with salt.

Another important part of the serving is the butter. After frying the veal patties, you add extra butter to the pan, let it melt and as it starts to bubble, you pour it over the patties and serve immediately. No pressure, but according to Carlsson, the butter should still bubble when you serve the guest.

How to cook perfect Wallenbergare veal patties

Remember the one trick to making this work: keep all the ingredients cold before you start. Also, do use a hand mixer or stand mixer if you have one. Here’s a version adapted from Tore Wretman’s “original” recipe.

250 g (1/2 pound) minced veal

3 yolks

2 dl (4/5 cup) heavy cream

salt

white pepper

breadcrumbs

a large knob of butter (for browning and pouring over)

For frying: butter

For serving: potato purée and browned butter. Optional: small green peas, lingonberry jam.

- Make sure the ingredients are cold. Turn the oven on 150°C (300°F).

- Blend the minced veal, yolks, salt, and white pepper together in a large bowl using a hand mixer or stand mixer. Add the cream in a stream. If you don’t have a mixer, stir by hand, adding the cream little by little and making sure to stir it in before adding more.

- Shape the batter into four large patties. If they don’t come together well, chill them.

- Put the breadcrumbs on a plate and coat the patties with the crumbs.

- Melt some butter in a frying pan on medium heat. Fry the patties until the surfaces are getting a little bit of color.

- Place the patties on an ovenproof dish and bake them in the oven until they are cooked through, for about 5-8 minutes. If you prefer, you can skip this step and just fry them until they are done.

- As you bake the patties, use the same frying pan to brown a large knob of butter. Pour the butter over the patties as you serve them. The popular way to serve it is with mashed potato, lingonberry jam, and small green peas.

Suggestions

Remember — lingonberries are completely optional. If you don’t have them, you’ll just be serving a dish closer to the original version.

0 Comments